How we classify medicines based on ingredients and excipients

- 1. Beyond the Active Ingredient: Why Excipients Matter

- 2. Why Excipients Can Be Problematic

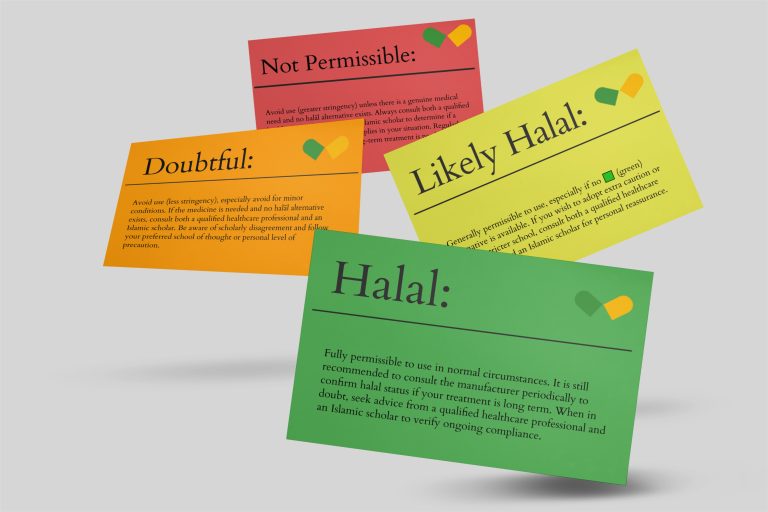

- 3. A Four-Category, Colour-Coded Classification

- 4. An Inclusive, Madhhab-Sensitive Methodology

- 5. Why the Ḥanafī School Is Our Reference Point

- 6. Mapping the Sunni Tradition Responsibly

- 7. Considering Contemporary Fiqh Council Resolutions

- 8. For Those Who Do Not Follow a Single Madhhab

- 9. Guidance for Shīʿa Users

- 10. A Rigorous Yet Pastoral Approach

- Which Islamic jurisprudential (fiqh) schools (madhāhib) are most widely followed around the world?1

- Our Classification

- Our Approach to Halal certifications

1. Beyond the Active Ingredient: Why Excipients Matter

When assessing whether a medicine is halal (permissible) or haram (impermissible), we look beyond the main active ingredient. Most medicines also contain excipients- inactive substances added to aid the medicine’s effectiveness, stability, absorption, or palatability. These include binders, fillers, coatings, preservatives, solvents, and flavouring agents.

2. Why Excipients Can Be Problematic

Some of these excipients may be derived from ethanol-based or animal-based sources. This raises important considerations for Muslim patients who wish to adhere to halal dietary requirements.

3. A Four-Category, Colour-Coded Classification

In order to guide Muslims who follow a halal diet, we classify excipients into four colour-coded categories. These reflect a combination of:

- classical Islamic legal rulings (fiqh),

- contemporary scholarly opinions, and

- real-world pharmaceutical practice.

4. An Inclusive, Madhhab-Sensitive Methodology

Appreciating the diversity of Islamic jurisprudence and recognising that most Muslim laypersons do not identify strictly with any single school, we adopt an approach that foregrounds the opinion of the predominant school while also incorporating the perspectives of the other Sunni schools. This ensures balance, accessibility, and inclusivity.

5. Why the Ḥanafī School Is Our Reference Point

In practice, most Muslims around the world are not formally trained in the madhhab system and instead follow the predominant view that is recognised and practised within their local community. The Ḥanafī school provides a natural reference point for our work because

- it represents one of the most widespread followings across the Muslim world, particularly in South Asia, Central Asia, and Turkey (see Table).

- Relative to the other Sunni schools, it remains predominant both in numbers and in its rich juristic legacy on matters of food, medicine, and everyday practice.

For this reason, our categorisation system is naturally aligned with the Ḥanafī approach, while also engaging with the views of the Mālikī, Shāfiʿī, and Ḥanbalī schools to ensure a balanced presentation without prejudice. This approach does not diminish the importance of the other schools.

6. Mapping the Sunni Tradition Responsibly

By situating the Ḥanafī position as a reference point and then noting the agreements or divergences of the other madhāhib (schools), our classification offers an accessible map of the Sunni legal heritage. This allows users from different backgrounds to navigate responsibly, with clarity on both

- the majority view and

- the alternative positions recognised within the tradition.

7. Considering Contemporary Fiqh Council Resolutions

We also take into account the resolutions of contemporary fiqh councils around the world. When it comes to dietary rulings in particular, the majority of these councils tend to adopt the predominant view, often aligning with the Ḥanafī position. However, some councils may take differing approaches, which can make navigation complex for the average Muslim. Our system has therefore chosen to rely on the sunni school approach for better clarity and ease of navigation. This approach maintains the range of contemporary scholarly opinions while highlighting the most widely adopted positions.

8. For Those Who Do Not Follow a Single Madhhab

We further recognise that some Muslims today adopt a methodology that does not bind them to a specific school. For them, our framework remains useful, as it presents the spectrum of opinions across the Sunni schools and equips them to make informed decisions, ideally in consultation with their trusted local imams and scholars.

9. Guidance for Shīʿa Users

Finally, we acknowledge our Shīʿa brothers and sisters. Although our framework is not specifically designed around the diversity of Shīʿa jurisprudence, due to limits of our expertise and capacity, more than 95% of rulings in practical matters of food and medicine overlap with Sunni outcomes. In the few cases where differences exist, we recommend that Shīʿa users use our system as a reference point and then seek specific guidance from their own scholars.

10. A Rigorous Yet Pastoral Approach

By taking this structured yet inclusive approach, we aim to reflect the scholarly richness of the Islamic legal tradition while addressing the practical realities of Muslim life today. Our system is designed to be both academically rigorous and pastorally sensitive, serving the needs of the widest possible audience.

Which Islamic jurisprudential (fiqh) schools (madhāhib) are most widely followed around the world?1

| School of Law | Estimated Global Following | Main Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Ḥanafī | Largest (~40–50%) | South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), Central Asia, Turkey, Balkans, parts of the Middle East |

| Shāfiʿī | ~20–25% | East Africa (Somalia, coastal Kenya), Yemen, Indonesia, Malaysia, Southern Thailand, parts of Egypt |

| Mālikī | ~15–20% | North and West Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, parts of Nigeria, Mali, Senegal) |

| Ḥanbalī | ~5% | Mainly Saudi Arabia, parts of Qatar and UAE |

| Jaʿfarī (Imāmī Shīʿa) | ~10–15% of all Muslims | Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, parts of Lebanon, Pakistan |

Our Classification

We aim to support conscientious and well-informed decision-making. In cases where there is genuine scholarly disagreement or insufficient clarity, we present the matter transparently—allowing each individual to act according to their conscience, school of thought, and specific health circumstances.

This system is not meant to create anxiety, but to tailor this service to Muslims and non-Muslim health care professionals who also want to better serve Muslims with clarity and confidence, ensuring that medical treatment remains ethically grounded and religiously sound.

| Category | Description | Explanation | Advice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 🟥 Not Permissible (Red) | This category includes ingredients or excipients derived from sources that are explicitly prohibited in Islam and unanimously agreed to be impermissible | This category refers to ingredients / excipients such as pigs, certain insects, or animals not slaughtered according to Islamic law, where there is Islamic juristic agreement of prohibition by all and there has been no transformation (istihalah). Examples typically include: • Non-transformed porcine-derived ingredients — unanimously agreed to remain impure by all. | This is a more binding ruling to avoid. Speak to your doctor first: Discuss whether avoiding the medicine is medically safe for you. Only apply the greater stringency to avoid use if your doctor confirms that avoiding the medicine will not harm your health. Seek religious guidance: Consult an Islamic scholar if you want faith-based advice, noting that levels of stringency may differ between scholars. Decide and review: Make your choice based on medical guidance and any religious advice; revisit your decision if your health condition or circumstances change. |

| 🟧 Doubtful (Amber) | This category includes ingredients or excipients whose sources are either: • generally prohibited by most scholars (with a minority permitting), or • doubtful due to unclear origins, warranting caution. | This category refers to ingredients / excipients that • come from a prohibited source (such as pigs or animals not slaughtered according to Islamic law) but there is a possibility according to a minority opinion, that it has undergone a significant legal transformation (istihala) that may make it legally pure (tahir) and halal. • However, majority scholars disagree on whether that transformation is complete or acceptable under Islamic law, or there is not enough information available to make a confident decision about its transformation and hence caution is advised. Because of this disagreement, there is no clear answer — so the excipient falls into the “doubtful” category. Islamic law teaches religious precaution (iḥtiyāṭ) when there is uncertainty. This category reflects: • Real-world gaps in ingredient/excipient transparency, • Scholarly disagreement on transformation, • And the difficulty of verifying every detail in modern pharmaceutical production. This category avoids mislabelling an ingredient as fully haram or fully halal when the evidence is incomplete or debated | This is a less binding rule to avoid. Speak to your doctor first: Discuss whether avoiding the medicine is medically safe for you. Only apply the lesser stringency to avoid use if your doctor confirms that avoiding the medicine will not harm your health. |

| 🟨 Likely halal (Yellow) | This category includes ingredients or excipients whose sources are generally permitted by most scholars, though a minority consider them prohibited. | This category refers to ingredients / excipients that may initially raise concerns but do not retain prohibited status, intoxicating effect, and / or legal impurity (najasah). Examples typically include: • Animal parts not considered legally impure (tahir), such as bones or certain enzymes (like calf rennet), even if the animal was not Islamically slaughtered according to majority Hanafi opinion. • Ethanol in small amounts that is non-intoxicating (non-khamr), sourced from non-wine origins, and serves a functional — not consumable — purpose. When the exact source or concentration is unknown, it generally meets the conditions for permissibility in Islam as it will not intoxicate, according to majority opinion. These excipients may originate from questionable sources, but the majority scholarly opinion rules them permissible. Nevertheless, some differing opinions exist. | Generally permissible to use, especially if no 🟩 (green) alternative is available. If you wish to adopt extra caution or follow a stricter school, consult both a qualified healthcare professional and an Islamic scholar for personal reassurance. |

| 🟩 Halal(Green) | This category includes ingredients or excipients from sources that are explicitly permissible in Islam and unanimously agreed to be allowed. | This category refers to ingredients / excipients which are plant-based, synthetic, or halal-certified as not containing any prohibited ingredients or excipients, with no impurity concerns. Examples typically include: Plant extracts, minerals, synthetic compounds, or animal derivatives certified halal due to halal slaughter. These excipients meet Islamic legal criteria for permissibility, and their use is widely affirmed by classical and contemporary scholars. While absolute certainty of cross-contamination cannot be guaranteed, prevailing industry standards suggest that any such contamination is either absent or negligible. In Islamic jurisprudence, this falls under the principle that hardship brings ease (al-mashaqqah tajlib al-taysīr), allowing for leniency in such cases. | Fully permissible to use in normal circumstances. It is still recommended to consult the manufacturer periodically to confirm halal status if your treatment is long term. When in doubt, seek advice from a qualified healthcare professional and an Islamic scholar to verify ongoing compliance. |

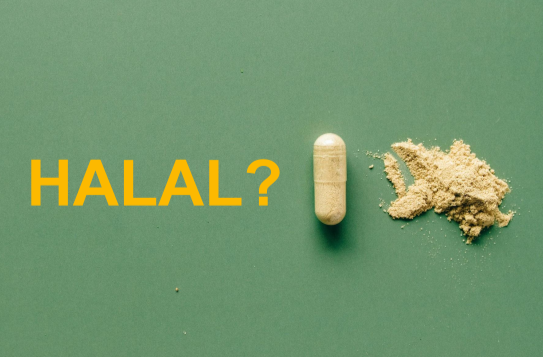

How We Assess Manufacturing Processes for Halal Classification

When determining whether a medicine is halal (permissible), we aim to look beyond just the list of ingredients and excipients. The entire manufacturing process also plays a crucial role. Even if all listed components appear halal, how the medicine is produced, handled, stored, or transported can still raise concerns — particularly the risk of cross-contamination with haram substances, such as khamr-derived ethanol or impermissible animal-based materials. However, our judgment can only be based on the information made available to us, and we remain limited when such details are unclear or would cause undue hardship to verify.

Ethanol Use in Pharmaceuticals

Ethanol, for example, is widely used in pharmaceutical manufacturing-as a solvent, preservative, or sterilising agent. However, its presence does not automatically render a medicine impermissible, since “ethanol” is not necessarily equivalent to khamr (wine or fermented grape-based alcohol) as defined in the Qur’ān.

Islamic jurists distinguish between types and uses of ethanol, especially in medical contexts. Key considerations include:

- The source of ethanol (synthetic or naturally fermented)

- The quantity present in the final product

- Its purpose in the formulation

- Whether it is evaporated or removed during processing

In many cases, particularly when the ethanol is present in trace amounts, serves a non-consumable function, or when no effective alternative exists—its use is deemed permissible under Islamic legal principles.

Transparency Challenges in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Despite our best efforts, full transparency about pharmaceutical production processes is rarely attainable. Companies often do not disclose complete information, and what is provided may be ambiguous, indirect, or overly technical. Moreover, it is logistically and financially unfeasible to conduct on-site inspections for every product, and large portions of the global pharmaceutical supply chain remain opaque and difficult to audit.

Our Method: Navigating Dīn and Health

In light of these realities, our classification relies on:

- Islamic legal principles of predominant probability (ẓann ghālib)

- Expert consultation in Islamic jurisprudence and pharmaceutical science

- A commitment to ethical, cautious, and medically responsible guidance

We do not require absolute certainty that cross-contamination with haram substances is completely absent. Based on prevailing industry standards, we assume that in most cases, such contamination is either non-existent or negligible. Where verification is impractical or unavailable—and there is no clear evidence of impurity—we apply the Islamic legal maxim:

“Hardship brings ease” (al-mashaqqah tajlib al-taysīr)

This approach ensures a balanced application of Sharīʿah, honouring both the principle of ḥifẓ al-nafs (preserving life and health) and ḥifẓ al-dīn (preserving religious integrity), without placing undue burden on individuals or the wider community. In cases of doubt, scholars generally advise following the principle of istiḥsān (juristic preference) or istiṣḥāb (presumption of permissibility) where appropriate, balancing diligence with feasibility.”

Our Approach to Halal certifications

Many pharmaceutical manufacturers provide halal certification for their medicinal products. Our approach to these certifications is governed by both legal reasoning and practical considerations:

- We accept halal certifications as valid when the source is non-animal based, unless there is compelling and credible evidence to the contrary. Such ingredients are categorised as 🟩 Halal (Green).

- If an ingredient or excipient is known to be animal-derived and the certification aligns with the majority scholarly opinion, we categorise it as 🟨 Likely Halal (Yellow). If the certification relies on a minority opinion, it will be categorised as 🟧 Doubtful (Amber).

- For cases like calf rennet, if it is unclear whether it is used in the production of lactose or other dairy derivatives, but the final product is certified halal, this typically reflects the majority view and is categorised as 🟨 Likely Halal (Yellow).

- While we cannot independently verify the reliability of every certifying body, we apply the principle of ḥusn al-ẓann — assuming good faith and integrity unless proven otherwise.

- We recognise that constructive engagement with existing certification systems serves the public good, while also acknowledging their limitations and areas for improvement.

References

- Pew Research Center. The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity (August 9, 2012).

– Executive summary at Pew website and full PDF; https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/08/09/the-worlds-muslims-unity-and-diversity-executive-summary/

↩︎