Ethanol in medicines

This resource explains the use of ethanol in medicines and outlines the Islamic rulings on its permissibility.

What is ethanol and how is it used in medicines?

Ethanol (also known as ethyl alcohol) is a type of alcohol and the active substance that causes drunkenness if consumed at high levels. Ethanol is used to make:

- Alcoholic beverages like beer, wine, and spirits

- Perfumes and toiletries

- Disinfectants and hand sanitisers (sprays and gels)

- Medicines.1

- Fermentation of biomass (e.g. various plant materials such as trees, grass, grains, sugarcane, dates, grapes and fruits etc)2 3 4

- Hydration of ethene from crude oil using steam (process used to make synthetic ethanol).5

Note: Not all alcohols are suitable for consumption e.g. methanol (used in antifreeze) and isopropanol (used as rubbing alcohol). Ethanol is the only type of alcohol that is safe for human consumption in moderate amounts.6 For information on other types of alcohol, see our resource on other synthetic alcohols (link).

Ethanol is used in medicines as:

🕌 Islamic ruling on ethanol

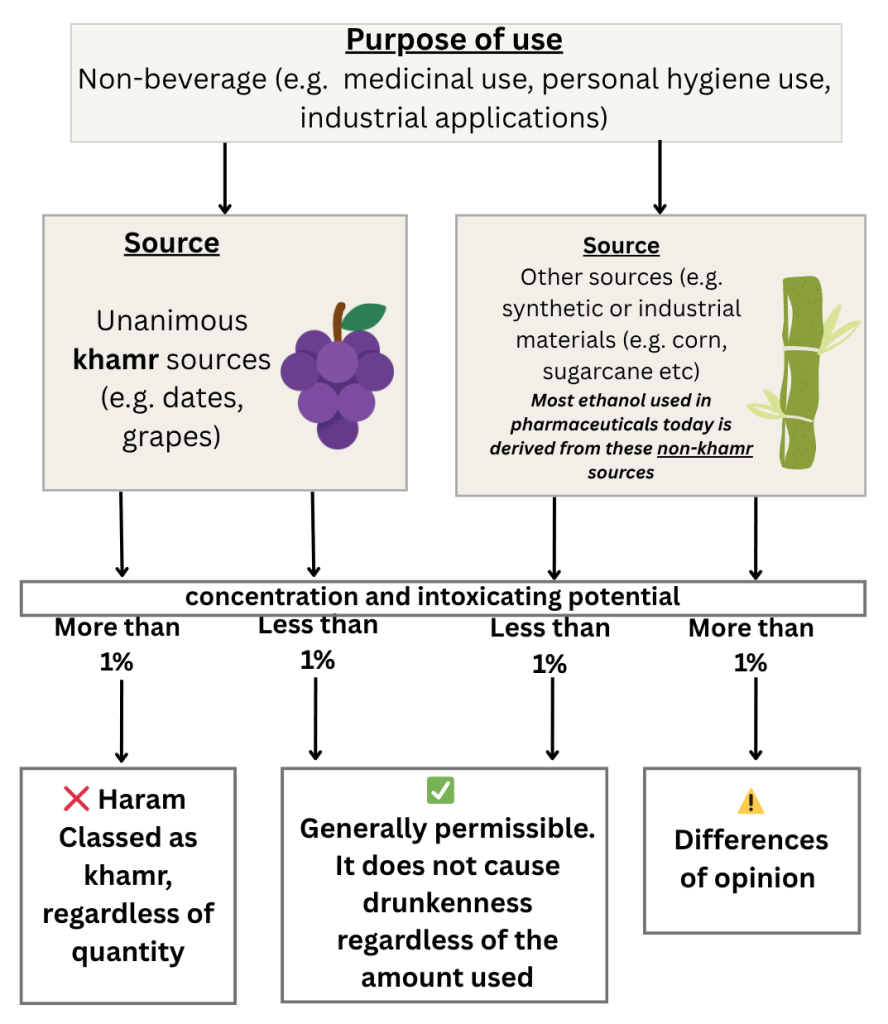

The Islamic ruling on ethanol depends on several key factors6:

1. Purpose of use

The intended use of ethanol is a key factor in determining permissibility:

- ❌Beverage and recreational use: Always haram (prohibited).

- ✅Non-beverage or medicinal use: Permissible according to the majority* of scholars if the ethanol is non-intoxicating and the medicine serves a genuine therapeutic purpose

2. Source of ethanol

- ❌Prohibited sources (Ashriba Arbaʿa): Ethanol from grapes, dates, raisins, or their juices is classed as khamr and haram if present in more than trace amounts (>1%).

- ✅Other sources (e.g., corn, sugarcane, wheat), or synthetic sources-lab-produced ethanol (not from fruit fermentation). Most ethanol used in pharmaceuticals today is derived from these non-khamr sources. According to the majority of scholars ethanol from such sources is considered halal for medicinal purposes if it does not intoxicate in the amount used.

3. Concentration and intoxicating potential

- Many scholars consider ethanol permissible when present in such small quantities that it cannot intoxicate even if consumed in large amounts (<1%).

- High or toxic concentrations are considered mufsid (toxic). Many scholars allow it to be used externally or for medicinal purposes in safe, therapeutic dosages.

To understand more about the ruling such as⚠️ differences of opinion, and what we mean by *’majority’ click the button below.

Ruling on Ethanol in Non-Beverage Uses

Ethanol that is:

- Used for medicinal or industrial purposes,

- Produced from non-khamr sources (e.g., synthetic or petrochemical processes), and

- Non-intoxicating in the amount used,

is generally considered halal (permissible) by the majority of scholars.

Khamr vs. Muskir: The Broader Ruling on Intoxicants

While khamr refers specifically to intoxicating drinks made from the four classical sources (grapes, dates, raisins, or their juice), the term muskir refers more broadly to any substance that causes intoxication, regardless of its source or form.

- Khamr: Always haram (forbidden) in all forms and quantities, even in small amounts.

- Muskir: Any intoxicating substance (liquid, solid, or vapor) is also haram if it intoxicates, but rulings depend on use, quantity, and context — for example, medical need or necessity (hajah and darurah) or trace, non-intoxicating levels may be excused.

Thus, not all ethanol is khamr, and not all khamr-related rulings automatically apply to ethanol, especially when it is synthetic, non-beverage, or used in minute, non-intoxicating amounts.

However, misusing such products — either by consuming those meant for external use or taking excessive amounts e.g. consuming hand sanitizer, may render them mufsid (toxic), and such misuse is prohibited both Islamically and medically.

Here are some examples of topical and medicinal products (i.e. non-beverage use) that may contain ethanol, their classifications and rulings (list not exhaustive):

| PRODUCT AND % OF ETHANOL | CLASSIFICATION | RULING |

|---|---|---|

| Antiseptic solutions and disinfectants 70-90% ethanol | Majority opinion: Permissible (halal) for medicinal use, as it is derived from non-khamr sources (e.g., corn, sugarcane, synthetic) and is considered tahir (pure) if non-intoxicating in the amount used. Minority opinion: Permissible only if no suitable halal alternative is available (darurah or necessity). Alternate view: Some scholars classify it as ⚠️ mufsid (harmful and toxic) if consumed unnecessarily, and permit its use strictly within therapeutic dosage limits and under medical advice. | ✅ Permissible (if used as directed by the manufacturer) |

| Cough syrups 10-20% ethanol |

||

| Hand sanitisers (e.g. gels and sprays) 50-70% ethanol |

||

| Mouthwash and oral applications (e.g. oral sprays, lozenges and gels) 20-30% ethanol |

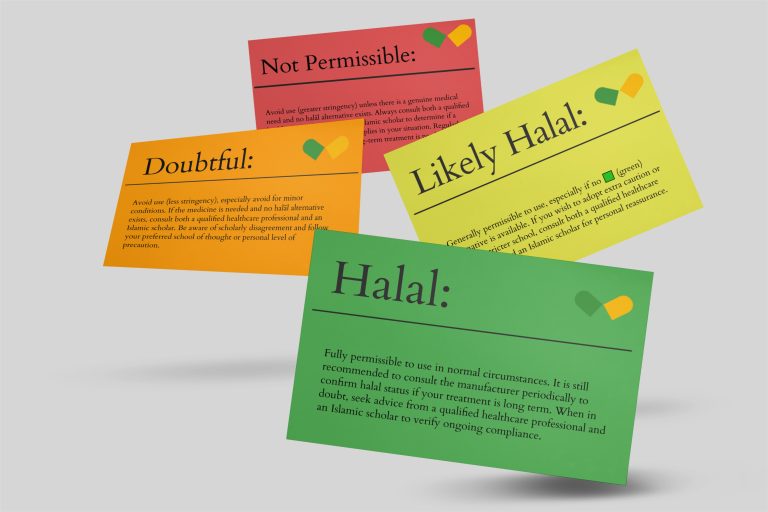

If you are unsure about taking or using medicines containing ingredients and/or excipients from haram sources, seek guidance from a practising Muslim HCP such as a pharmacist or doctor. Alternatively, consult your local Imam or a trusted Islamic scholar, ideally one who has knowledge and expertise in the fiqh (Islamic rulings) of medicine.

💭Did you know?

Even if a medicine contains an excipient from a haram source, it may still be permitted in certain cases. Here are three Islamic maxims (principles):

- Medical need or necessity (hajah or darurah): Under this principle, if there is a medical necessity, such as an emergency situation, or where there is a strong chance the individual’s health will deteriorate, and if no viable halal alternative is available, then it is permitted to take a medicine containing ethanol that meets the conditions of being haram, until a viable halal alternative becomes available.

- An impermissible medicine becomes permissible if five conditions are fully met (click here to learn what the five conditions are).

- Hardship begets facility (al-mashaqqa tajlib at-taysir): Under this principle, if applying religious practice becomes too burdensome or creates hardship, then leniency can be applied to ease it (click here to read more). If you have tried your best to seek an alternative halal medicine and it becomes too difficult for you, this principle allows you to take/use the medicine you have been prescribed/supplied.

⚠️ Important information for patients

- Always take or use your medicine(s) exactly as directed or prescribed by your healthcare professional (HCP), such as your doctor or pharmacist

- Do not stop, delay, change or alter the way you take or use your medicine(s) without first discussing it with the HCP who prescribed or supplied it to you

- Always consult your HCP if you have any questions or before making any decisions about your treatment

- For Islamic guidance, seek advice from your local Imam or a trusted Islamic scholar – ideally someone with relevant knowledge and expertise in the fiqh (Islamic rulings) of medicines

- Use the information gathered to make an informed decision together with your HCP and, if needed, your local Imam or trusted Islamic scholar.

FAQs

Disclaimer

- This resource is for educational purposes only. It does not constitute clinical, medical, or professional healthcare advice and should not replace individual clinical judgement or qualified religious guidance

- Always consult your doctor, pharmacist, or other healthcare professional regarding your own medical conditions or for advice on treatment options

- Healthcare professionals remain fully responsible and accountable for decisions made within their own scope of practice

References and further reading

- UK Health Security Agency. Ethanol: general information. [online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ethanol-properties-uses-and-incident-management/ethanol-general-information [Accessed 30th April 2025] ↩︎

- Alternative Fuels Data Center. Alternative Fuels Data Center: Ethanol Feedstocks. [online] Available at: https://afdc.energy.gov/fuels/ethanol-feedstocks [Accessed 30th April 2025] ↩︎

- Ahmad A, Naqvi SA, Jaskani MJ, Waseem M, Ali E, Khan IA, Faisal Manzoor M, Siddeeg A, Aadil RM. Efficient utilization of date palm waste for the bioethanol production through Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. Food Sci Nutr. 2021 Feb 21;9(4):2066-2074. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2175. ↩︎

- Chitranshi R, Kapoor R. Utilization of over-ripened fruit (waste fruit) for the eco-friendly production of ethanol. Vegetos. 2021 Feb;34(1):270-276. doi: 10.1007/s42535-020-00185-8. ↩︎

- BBC Bitesize Making chemicals on an industrial. [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zwjsk2p/revision/6 [Accessed 30th April 2025] ↩︎

- Shaykh Rafāqat Rashid. Revising The Fiqh of Khamr and Alcohol: Ethical Use from an Islamic Perspective. Al Balagh Academy. 2024 May. Available at: https://www.albalaghacademy.org/blog/revising-the-fiqh-of-khamr-and-alcohol/ ↩︎

- European medicines agency. Questions and Answers on Ethanol in the context of the revision of the guideline on ‘Excipients in the label and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use’ (CPMP/463/00) [online]. Available at: https://www.gmp-compliance.org/guidelines/gmp-guideline/eudralex-volume-3-questions-and-answers-on-ethanol-in-the-context-of-the-revision-of-the-guideline-on-excipients-in-the-label-an [Accessed 30th April 2025] ↩︎

- Ref Chung E, Reinaker K, Meyers R. Ethanol Content of Medications and Its Effect on Blood Alcohol Concentration in Pediatric Patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Apr;29(2):188-194. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-29.2.188. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11001219/ ↩︎

- European medicines agency. Questions and Answers on Ethanol in the context of the revision of the guideline on ‘Excipients in the label and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use’ (CPMP/463/00) [online]. Available at: https://www.gmp-compliance.org/guidelines/gmp-guideline/eudralex-volume-3-questions-and-answers-on-ethanol-in-the-context-of-the-revision-of-the-guideline-on-excipients-in-the-label-an [Accessed 30th April 2025] ↩︎

- Ref Chung E, Reinaker K, Meyers R. Ethanol Content of Medications and Its Effect on Blood Alcohol Concentration in Pediatric Patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2024 Apr;29(2):188-194. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-29.2.188. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11001219/ ↩︎